COOPERATION MODEL

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

PRODUCT ENGINEERING

DevOps & Cloud

LOW-CODE/NO-CODE DEVELOPMENT

INDUSTRY

FRONTEND DEVELOPMENT

CLOUD DEVELOPMENT

MOBILE APP DEVELOPMENT

LOW CODE/ NO CODE DEVELOPMENT

EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES

A three-decade-old programming language, yet heavily used in modern software development, Java consistently evolves to meet modern software demands, with each new Java version bringing significant updates. Introduced in 2014 in Java 8, Stream API is considered the most crucial update of all time.

Before Java Streams, devs had to write verbose code for data manipulation. This article will thoroughly explore the Java Stream API, why it is relevant today, and how to leverage it. As a Java developer understanding the Stream API is necessary, regardless of your experience or familiarity with Java.

Boost your Java app's performance and streamline development. Our expert team harnesses modern Java features like the Stream API to deliver efficient, scalable, and clean code. Hire Java developers today for real results.

To put it simply, the Java Stream API enables programmers to declaratively (you just describe what to do, not how to do it step-by-step) and functionally (using reusable operations) process data sequences.

Important points to remember:

A Stream in Java isn’t a container that stores data like a list or array. Instead, it’s more like a pipeline that takes data from a source (say, a collection or array) and lets you run operations on it, like filtering, mapping, or reducing. These are called aggregate operations because they work across the whole sequence rather than on individual elements one by one.

With Streams, you can run operations one after another or split them across multiple CPU cores for speed. Furthermore, you can link steps together (like filter → map → collect) to build complex logic in a relatively easy way.

Here’s a simple example:

List<String> names = Arrays.asList("Alice", "Bob", "Charlie", "David");

List<String> filteredNames = names.stream()

.filter(name -> name.startsWith("A"))

.collect(Collectors.toList());In this example, instead of writing a loop to check each name, you create a Stream from the list and then chain operations:

Here, the Stream handles the iteration. You just describe the condition and the final form you want, and the API takes care of the rest. The original list isn’t changed; you get a new list with only the filtered values.

In simple terms, Streams provide a practical approach to clean development. Here are the benefits:

Less Code: Complex data ops like filtering, mapping, and collecting can be expressed in fewer lines of code with the Java Stream API.

Improved Readability: You focus on what should be done rather than getting into each step.

Clean Pipelines: Stream pipelines are modular. You can chain together operations to process data in a linear way.

Lazy Evaluation: One of the lesser-known strengths is their laziness. Intermediate operations like filter() or map() are only executed when a terminal operation (like collect()) is called. Means unnecessary work is skipped.

Simple Processing: Streams make multithreading remarkably easy. The API can divide data across multiple CPU cores and run operations concurrently.

No Side-Effect: Streams leave the original data untouched. Instead, they return transformed data as a result.

Functional Programming Support: Java's Stream API works naturally with functional interfaces.

No Internal Storage: It doesn’t hold data itself. Instead, it acts as a pipeline for data to flow through.

Understanding the fundamentals of Java Streams is vital for developers before using them. Stream operations are categorized into two types

1.Intermediate Operations: These operations modify elements and produce a new one, allowing you to chain multiple methods together. Examples:

2. Terminal Operations: These operations execute the stream pipeline and return a result or side effect. Examples:

As you know, Streams don’t modify the original data; therefore, immutable. Means, they don’t have any side effects. Under the hood, Lazy Evaluation optimise the process by executing intermediate operations only after terminal operations. If the terminal ops fail, then it runs the intermediate ops.

It remains lightweight, as we have already mentioned that it doesn’t store elements, only acting as a conduit through which data flows.

The Stream API exploits the Fork/Join framework to split data into chunks, process them in parallel, allowing developers to execute parallel processing. Plus, Streams are tightly coupled with Java’s functional interfaces, enabling developers to use lambda expressions.

Creating a stream is as simple as calling the method. Here are the main ways to create Streams in Java.

From Collections

From Arrays

Using Stream.generate() and Stream.iterate()

From File or I/O Channels

Most commonly, streams are created from Java collections (like List, Set, or Queue).

These classes come with a built-in .stream() method:

List<String> names = Arrays.asList("Alice", "Bob", "Charlie");

Stream<String> nameStream = names.stream();To enable parallel processing, you can use .parallelStream() instead:

Stream<String> parallelStream = names.parallelStream();You can also use Arrays.stream() or Stream.of() to turn arrays into streams:

int[] numbers = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

IntStream numberStream = Arrays.stream(numbers);

Stream<String> streamOf = Stream.of("Java", "Stream", "API");For infinite or dynamically generated streams, Java provides factory methods like:

Stream<Double> randomNumbers = Stream.generate(Math::random).limit(5);

Stream<Integer> countStream = Stream.iterate(0, n -> n + 1).limit(10);Java NIO makes it possible to stream lines (useful for large files) directly from a file:

try (Stream<String> lines = Files.lines(Paths.get("data.txt"))) {

lines.forEach(System.out::println);

}Use .stream() for regular operations on lists or sets.

Use .parallelStream() when working with large datasets and your operations are independent (no shared mutable state).

Use Stream.generate() or Stream.iterate() for dynamically generated data or simulations.

Use Files.lines() for file-based pipelines in data processing or log analysis.

The following examples show how streams can streamline routine programming tasks.

Let's say you want to filter names that start with the letter "A":

List<String> names = Arrays.asList("Alice", "Bob", "Ankit", "Brian");

List<String> filteredNames = names.stream()

.filter(name -> name.startsWith("A"))

.collect(Collectors.toList());

System.out.println(filteredNames); // Output: [Alice, Ankit]Want to square each number in a list?

List<Integer> numbers = Arrays.asList(1, 2, 3, 4);

List<Integer> squares = numbers.stream()

.map(n -> n * n)

.collect(Collectors.toList());

System.out.println(squares); // Output: [1, 4, 9, 16]Imagine you have a list of Employee objects and need to retrieve the names of employees earning more than 50,000:

List<Employee> employees = Arrays.asList(

new Employee("John", 60000),

new Employee("Jane", 45000),

new Employee("Jack", 70000)

);

List<String> highEarners = employees.stream()

.filter(e -> e.getSalary() > 50000)

.map(Employee::getName)

.collect(Collectors.toList());

System.out.println(highEarners); // Output: [John, Jack]You can use reduce() to sum a list of integers:

List<Integer> numbers = Arrays.asList(10, 20, 30);

int sum = numbers.stream()

.reduce(0, Integer::sum);

System.out.println(sum); // Output: 60Reading lines from a file using Files.lines():

try (Stream<String> lines = Files.lines(Paths.get("input.txt"))) {

long count = lines

.filter(line -> line.contains("error"))

.count();

System.out.println("Number of error lines: " + count);

} catch (IOException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

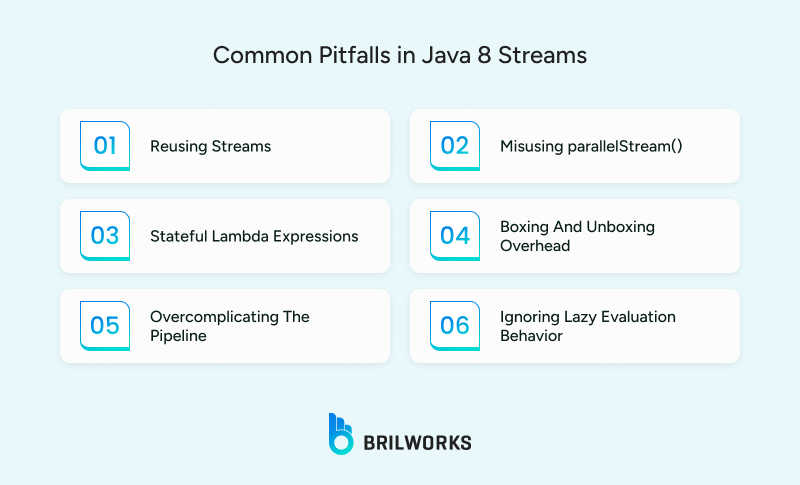

They are not infallible, and can be easily abused by developers unfamiliar with functional programming. The following are some of the most typical errors to be aware of:

A stream can be consumed only once. Once a terminal operation like forEach() or collect() is called, the stream is considered "used up." Attempting to reuse it will throw an IllegalStateException.

Stream<String> stream = Stream.of("A", "B", "C");

stream.forEach(System.out::println);

stream.count(); // Throws IllegalStateExceptionIt might seem like a quick win to add .parallelStream() for performance boosts, but it’s not always effective. For small operations, it can slow things down.

Modifying external state in parallel streams can result in unpredictable results.

List<String> result = new ArrayList<>();

list.stream().forEach(result::add); // Not thread-safeUsing boxed types (Integer, Double) instead of primitives (int, double) can have performance issues in large applications. Use primitive streams (IntStream, DoubleStream) when possible.

Overly long stream pipelines can make maintenance harder. If you find yourself chaining 8+ operations in one line, it might be time to refactor.

Intermediate operations are lazy, they don’t execute until a terminal operation is called. Misunderstanding this can lead to confusion when debugging why nothing is happening.

Stream.of("x", "y", "z")

.filter(s -> {

System.out.println("Filtering " + s);

return true;

}); // Nothing prints because no terminal operation is presentRelying too heavily on complex stream pipelines without optimizing can create maintenance issues. It’s something that surfaces during Java app maintenance.

To write clean, efficient, and bug-free stream-based code, developers should follow a few tried-and-true best practices.

By enabling a clean, functional, and declarative style of programming, the Java Stream API simplifies complex transformations opens the door more testable code. In other words, Stream API in Java is a step toward building cleaner and more scalable solutions.

The Java Stream API, introduced in Java 8, provides a functional programming approach to processing sequences of elements. It helps write cleaner, more expressive code for tasks like filtering, mapping, and reducing data, all while improving readability and maintainability.

The Stream API enhances performance through lazy evaluation and support for parallel processing. This means operations are only executed when needed, and large data sets can be processed across multiple threads efficiently.

Yes, the Stream API can be used in Android development or any Java-based mobile environment. However, it’s important to be mindful of memory usage and performance on mobile devices, especially with large or nested streams.

Intermediate operations (like map() or filter()) transform or filter data and return another stream, allowing method chaining. Terminal operations (like collect() or forEach()) produce a result or side effect and mark the end of the stream pipeline.

No, Java Streams are not thread-safe by default. If you’re using parallel streams or accessing shared mutable data, you need to manage thread safety manually, typically using synchronization or concurrent data structures.

Get In Touch

Contact us for your software development requirements

Get In Touch

Contact us for your software development requirements